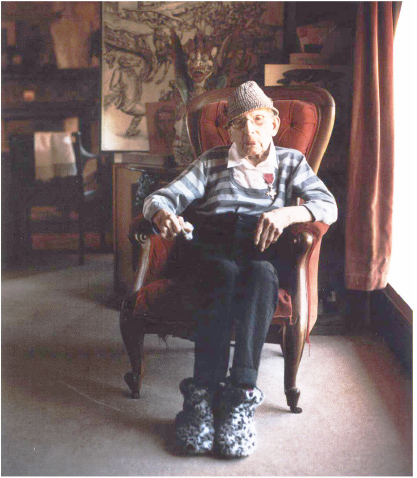

Stanley seated in his studio, in an early Victorian lady’s button-back chair.

Photography: Antony Crolla

Drawn from Life by Sacha Llewellyn

Centenarian Stanley Lewis looked back on his artistic output as a kind of ‘pictorial diary’, a social history down the decades. Till recently the work has been rolled up in cellars, hidden in sketchbooks or pinned up in his studio in the South Pennines. But now, as Sacha Llewellyn reports, a posthumous exhibition will at last bring to public view this rich personal chronicle of the 20th century.

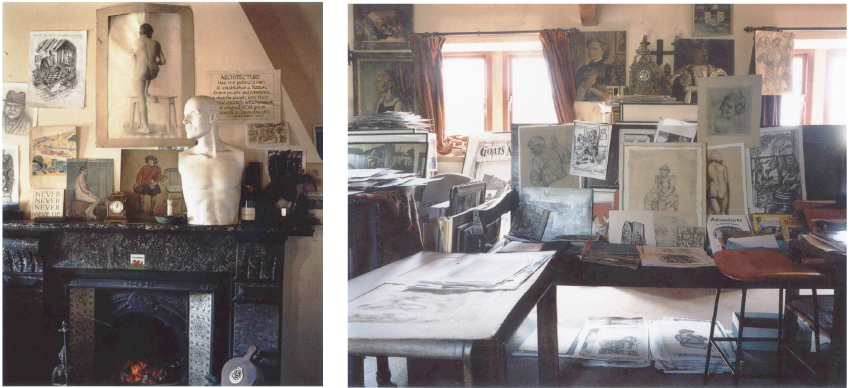

‘If you look at my work from the 1920s to the present day you can see the social history of each decade, a pictorial diary if you like – nothing is make-believe or fantasy, it is what I saw as I lived my daily life.’ From 2003 until his death in 2009 at the age of 103, Stanley Lewis lived at his daughter’s home in a large studio overlooking Yorkshire moorland, with ‘vast oak beams holding the roof up, and fabulous views. I sleep, eat, work, smoke, read, dream and meet visitors in my room. This is my world now – here I can be free,’ he said. He surrounded himself with thousands of his drawings and paintings (much of his life’s work), as well as art books and objects collected over a lifetime. ‘I call it organised chaos and I know exactly where everything is.’ In this room, Stanley shared his remarkable anecdotes – about his close friendship with Dylan Thomas, his encounters with Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, his recollections of World War I and II – with frequent visitors, his perfect memory effortlessly recalling the names of the characters who appeared in his canvases.

Stanley Lewis was born in 1905 on a large farm in Monmouthshire. His mother was fascinated by books and had a large collection ‘all marvellously illustrated’. From an early age, Stanley was captivated by these drawings and tried to imitate them. He would also spend hours ‘capturing the animals and all the things around me, and even the farm workers would remark: “Stanley is marvellous at drawing eyes.”‘ This passion for the land and animals remained a strong influence throughout his life.

Having spent three years at Newport School of Art, in 1926 Stanley entered the painting school at the Royal College of Art. Here his love of drawing flourished and he spent hours in the National Gallery copying old masters and in the British Museum drawing ancient statues and studying the prints and drawings in the Print Room. He had books on Rubens, Titian and Puvis de Chavannes stacked on his bedside table up until his death.

The early 20th century was a time of experimentation in British art. New styles and subjects expressed the changing dynamics of society, leaving behind the more traditional concerns of art. But the RCA reflected only the conservative outlook of its principal, Sir William Rothenstein, ‘a small, unobtrusive-looking man whose head hardly came above the edge of the table’. Along with his teaching staff (‘Hubert Wellington, Alfred Kingsley Lawrence, Randolph Schwabe, Colin Gill and Allan Gwynne-Jones [Wol Feb 1999] were among the teachers with whom I had a tremendously close contact’), Rothenstein instilled in his students the vital and basic need for disciplined technique, useful in every artistic style. Stanley’s meticulous skills were firmly rooted in this doctrine, and he remained grateful ‘to have studied art in the 1920s and spent years struggling to learn my craft the hard way’. The lack of ‘good old-fashioned drawing skills’ in art schools and modern painting is a subject close to his heart. ‘At least Banksy, the graffiti artist, has skill in the use of an aerosol, and his stencilling technique is second to none.’

Stanley became part of a strand of British 20th-century art which sought to breathe new life into narrative and landscape painting. ‘I felt an inner force burning to capture my world around me exactly as I saw it in the reality that it was.’ He took a detached view of the battle of styles raging in his day. ‘I couldn’t bear the new stuff. It all started with Dali and his Melting Watch… How can you make a good painting out of that subject?’ However, his disillusionment with modern art is mostly centred on how money takes precedence over talent. ‘Damien Hirst auctioned off his collection of stuffed and pickled animals and paintings and raised £111 million. Hirst should place himself and Saatchi in a tank of formaldehyde together with their millions and install it among a herd of cows. Now that would be more like it.’

In 1929 Stanley applied for a scholarship at the British School in Rome with Allegory, a large painting celebrating ‘country life and animals, and man’s respect for Nature’. He missed by one vote, ‘which made Augustus John furious’. He then assisted at the studio of A.K. Lawrence, but found his bouts of depression wearisome. ‘Lawrence had been in the trenches and had it rough.’ So he accepted a teaching post at the Newport School of Art, a move to which Sir William Rothenstein was fiercely opposed, feeling that Stanley should focus on his own art. Rothenstein wrote in a letter: ‘I am rather surprised at you applying for a full-time teaching post of a general nature.’ Coming from a farming family, Stanley had had the need to be a salaried working man instilled in him from early on, but ‘I felt cut off… and often wonder what would have happened to my art career had I stayed there [with Lawrence].’

Convinced that Stanley was still worthy of a Rome scholarship, Rothenstein persuaded him to enter one last time in 1930. He came a disappointing third, but it resulted in the epic canvas Hyde Park. Stanley appears centre stage, reclining with his artist’s satchel, while Muriel Pemberton, his first girlfriend (later head of fashion at St Martin’s School of Art), appears behind him. The Chinese paper parasol she’s holding Stanley ‘bought especially for the painting, to add a bit of colour’.

While Stanley was never an accredited war artist, his time spent in the Royal Artillery from 1939 gave him ample opportunity to paint. ‘I was always sketching – one of my army colleagues told me I’d better give that stuff up until the war was over. “Don’t be so bloody silly,” I said, “I’m an artist.”‘ In addition to drawing scenes of army life and portraits for soldiers to send home to their girlfriends, Stanley was also given commissioned work such as a commemorative oil painting of the bombing of the Tirpitz in Norway, now in the Fleet Air Arm Museum in Somerset.

In 1946, Stanley took the job as principal of Carmarthen School of Art, where he stayed until he retired in 1968. His marriage (to one of his students, Minnie Wright), his need to provide for three children and his 40-year teaching career all possibly prevented him from achieving his full artistic potential. ‘Sometimes I wonder how I managed to find the time for my painting. But my little pocket book and pencil kept my head straight, and I recorded everything that occurred around me.’

Until 2008, Stanley’s life’s work, including Allegory and Hyde Park, remained in his possession, nailed to the walls of various barns or rolled up in cellars. Their restoration has revealed a magnificent cycle of historically important works by an artist who deserves recognition. Now he is about to have his first exhibition. Asked whether, after 103 years, he would have liked more time to prepare, Stanley replied: ‘No, that’s fine!’

This article appeared on the occasion of the exhibition ‘The Unknown Artist. Stanley Lewis and his Contemporaries’ organised by LLFA in collaboration with the Cecil Higgins Art Gallery in 2010.