Fish and chips were not rationed. Consequently, fish and chips, which before the war had been seen as just a working-class food, made its way upward to become a food that all Britons ate. Your local chippie could also sell you meat pies, as they were not rationed, either — though the meat in them was more likely to be Spam than anything else.

A convoy of mobile canteens would move into bombed areas to feed residents and rescue workers for free, coordinated by the Ministry of Food. These mobile canteens were largely funded by donations from America.

The Ministry expected rationed home food to be supplemented by meals at work and at school. Before the war, only about 250,000 school meals a day were served; by the end of the war, school meals happened just about everywhere, feeding about 1,850,000 children a day. The Ministry made it compulsory for any factory over a certain size to open a canteen to feed its workers. The number of factory canteens consequently went from 1,500 in 1939 to 18,500 in 1945.

In July 1940, restaurant restrictions started coming into effect. The first regulation was that in one meal you could not have both a meat and fish dish. So a fish starter, and meat main course, was out.

In June 1942, two additional restaurant restrictions came into effect. The first was that no restaurant meal could have more than three courses. The second was that no restaurant could charge more than 5 shillings for a meal (alcohol and coffee excluded.) This had the desired effect, of course, of causing restaurants to be more frugal in what they chose to offer, or serve smaller portions of it, so that they could still make a profit on the meal. To ensure that restaurants didn’t just try to get around this through “cover charges”, the restriction also stipulated that the highest cover charge that would be allowed was 7s. 6d.

“You need no ration card for restaurants, although a waiter will serve only one meal to a person at a sitting, and that limited to three courses or five shillings expenditure. Swanky places get around the quality barrier by adding a stiff cover charge, but the three courses are never exceeded. A soup or hors d’oeuvres, an entree and a dessert are regulation. Coffee and drinks are extra. The maitre d’hotel or waiter may “save” a portion of joint for old customers, but a late diner will inevitably find the menu exhausted and only sausage or mushrooms available.” — Albin E. Johnson. Europe: Where the Cupboard is Almost Bare. Rotary International: The Rotarian. September 1943. Vol. 63, No. 3. Page 18.

Public eating centres called “British Restaurants” were set up across the country. The driving force behind their creation was a Mrs Flora Solomon, who was in charge of Marks & Spencer’s staff canteens at the beginning of the war. She was inspired by seeing the Londoners’ Meals Service, which London County Council started in September 1940 to feed those who had been bombed out of their homes. She gave the idea to Lord Woolton, whom she knew socially. He backed the idea, and asked her to get it started. She got permission from Simon Marks, one of the owners of Marks & Spencer, to use some of her work hours towards the setup.

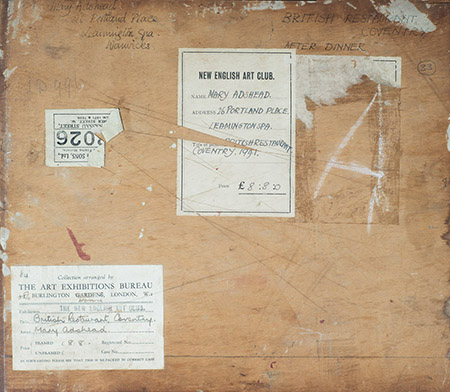

She set up the first “Communal Feeding Centre”, as she called it, in the Kensington area of London, using Marks & Spencer’s store personnel as staff, then set up one in Coventry after the blitz bombing it suffered on 14 November 1940. The Marks & Sparks store in Coventry had been bombed out; since the staff had nowhere to work, she pressed them into service for her Feed Centre there, as well. Her plan was that once the Communal Centres were up and running, they would be turned over to locals in the area to run.

One opened in Newcastle on 6 October 1941, with the Duchess of Northumberland and the Lord Mayor of Newcastle having lunch on the first day to help promote it. The menu there in 1941 was Soup 2d (1p); Meat with 2 Veg 7d (3p); Sweet 2d (1p); Cup of Tea 1d (¬Ωp).

Grace at the ‘Sausage Hatch’, British Restaurant, Coventry

Mary Adshead (1904–1995)

Herbert Art Gallery & Museum

Churchill liked the idea very much, but he didn’t approve of the name. He thought it smacked of socialism, and suggested “British Restaurants” instead, and so, as of January 1942, “British Restaurants” they were.

The restaurants were actually more like canteens. They were set up in church halls, town halls, school halls, etc, and run by Local Food Committees on a non-commercial basis. They would usually have restricted hours of opening, operating just at main meal times such as noon to 2:30 pm, etc

All meals were ration free. The only rule was that you could only have one serving of either meat, game, poultry, fish, eggs, or cheese. You couldn’t have two from that list at the same meal.

They were also relatively inexpensive. The set maximum price allowed was 9d, though even that would likely only have been charged in London where operating costs would be higher.

The British Restaurants served basic foods such as sausage, mash, gravy, or minced beef with parsnips, greens and potatoes. There was also pudding and custard.

Some of the British Restaurants supplied packed meals for working people such as miners. The British restaurant in Chopwell (in what is now Tyne and Wear County; previously Durham) advertised the following food to go: meat pies, sausage rolls or spam sandwiches at 4d each; ham or bacon sandwich at 5d; teacakes with butter and jam on them, 3d.

By November 1943, there were 2,145 British Restaurants. Less populous areas had Food Distribution Centres, popularly called “Cash and Carry Restaurants”; they were supplied by a British Restaurant in a larger area.

Any food waste from the restaurants went to local pig clubs.